Quilt History 1700-1900's

Quilt History 1700-1900's

The textiles of the North America is totally different from its European cousin. The growth of the land, the composition of the soil, the total land area caused a textile tradition totally different from its European cousin. This comes as a surprise because so much of the technology and design of the textiles came from Europe.

For a nation to be able to produce its own textiles and textile tradition there is a huge demand for people. As the United States was in its developing stages the general population was quite small. That meant that only those who had a specialized trade could come to the United States. There was a huge demand for blacksmith's. Well diggers. Smiths of different trades. Furriers. Carpenters.

Labor shortages caused much of the growth to be slow. Let's face it...the idea of moving from a European country to come to America was scary. Not a lot of people came here initially. It wasn't until the early settlers who did face the dangers of crossing the Atlantic Ocean, let alone landing in a totally strange land with Native Americans, were able to write home and announce that they were becoming rich. (The Native Americans were oft portrayed as buckskin wearing savages...collectors of human scalps.)

By about 1800 there were enough people to encourage industry. By 1850 America finally overcame its labor shortage equaled Britain's population. By 1870, the population surpassed Britain by 8,500,000. By 1870 there were 40,000,000 Americans were found in the rural areas. The quick growth of Americans meant that the land area also grew to 37 States. That meant that the land area grew from 1,750,000 to 2,970,000 square miles!

Thousands of new settlers went west to develop new communities. That meant that the new immigrants (largely Irish and French Canadians went to work in the mills

The 1870's also marked the beginning of a forty year period of extensive immigration, with some 40,000,000 people (from Central and eastern Europe) landed in the United States. Providing labor to fuel the growth of the textile industry, few could afford to homestead or claim staking. About two thirds of the late 19th century population lived in rural areas and were supplied with textiles by an extensive railway network, those who tended the mill machines remained in dense populated areas. The response to the conditions, both within and outside the textile industry, drove America towards social legislation, labor laws and increased technology.

By 1700 France believed that it was proprietor of almost of our country! Except for the southern most regions stretching from Florida to California (these were claimed by the Spanish crown) and the British held colonies around Hudson Bay and the Atlantic coast. French claims were later abandoned to the British and Spanish in 1763.

The European nations prized America for its natural resources. French and English took substantial catches from the sea, furs came from the northern interior, so did timber, tobacco from Virginia was so prized in London that was used as a currency by tobacco growers.

The future of America rested on her exports of raw materials. Returning ships were laden with manufactured goods, including textiles. America needed canvas for ships' sails, jute sacking, ropes, cords and other utilitarian cloths...the most numerous until the Revolution were wool fabrics, essential as protection from the winter climate in northern settlements. The preponderance of wool cloth was not solely due to climate. They represented Britain's most well established and fiercely defended textile industry Protection of the woolen trade (these laws were not created solely for the woolen trade) was offered by a series of British Acts passed between 1650 and 1696 that stipulated that all but specially licensed foreign ships were barred from the colonies and that goods must arrive in England in ships belonging either to Britain or the country of origin. The Navigation Act of 1660 proved the value of North American raw materials to the British textile trade for tobacco, sugar and ginger, it ensured that indigo, fustic and cotton were not to be transported out of the empire.

Britain thought that it had a grip on the throat of the America's Dutch and French goods were being smuggled into American ports.

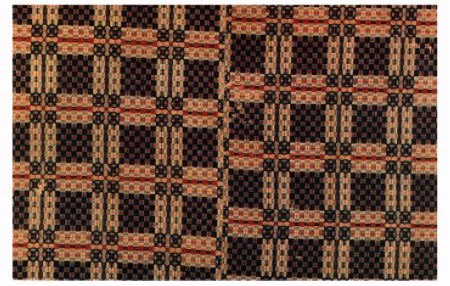

18th century linen checks believed to be of European construction.

They were found in Pennsylvania and are typical of the patterns associated with German weaves, which were widely copied in America as they employed coarse yarns.

Since Britain did not make a full range of cloths, British merchants imported floral brocaded dress silks, and vividly colored, striped and brocaded worsted calamancoes (also for clothing) were most probably from Norwich, imported furnishing silks were likely to be imported from Italy who in turn, provided silk damasks used by English upholsterers. India provided the world's most finely spun and vividly patterned washable cottons until the 1770's to both Britain and the America's.

The coronation in 1714 of the hanoverian King George 1 (1660-1727) caused an increased British trade in Prussian and German textiles. Thus, Osnaburg and Ticklenburg came to America with fine linens from Holland and northern France. Later Ireland began to develop its own textiles based on the flax seed that grew in abundance in America. Both jute and flax grew with great abundance. Both grew so much that in the middle of the 18th century America was sending tens of thousands of bushels of flax seed to Ireland.

In the early 17th century James 1 (1566 to 1625) sponsored the planting of mulberry trees in Jamestown, Va. Virginia continued to be a source for silk in the 18th century but produced less silk than Georgia (made a separate colony in 1732). And the Carolinas (where refugee Huguenots established in the 1680's were said to be the first to weave mixed silk goods. In 1730 settlers were granted free land for planting 100 mulberry trees for every 10 acres cleared.

Georgia was the most active of all of the southern colonies in the area of silk worm raising. In fact silk worm farmers and experts came from Italy and England in 1732. Pennsylvania began to grow silk worms in the 1720's within 10 years Pennsylvania cocoons were said to produce a cloth equal to that of the French and Italian looms. The best results came when the silk was sent to England for weaving.

In 1749 Britain removed the import duty for colonial silks reeling mills (the process of removing the silk from the cocoon) were found from Pennsylvania to Savannah, Georgia.

By 1759 10,000 pounds of silk fiber was sent from Georgia to England! Connecticut began silkworm rearing and established a lead that held until the 1830's.

During 1750's cotton slowly replaced silk as the fiber crop of the South. Until the 1790's cotton growing was more time consuming to prepare than silk or flax. Flocks of sheep were being imported by the 1700's provided both wool and food. Cloth could easily be imported and food not, wool was a secondary product from sheep until the 1800's when merinos were imported for their fine quality fleece.

With so much available raw materials it was difficult for Britain to stop textile manufacture, despite drastic measures as disincentives placed on Virginia manufacture in 1628, the bans on woolen cloth (including to other colonies) in 1699, and the outright outlawing of weaving in the Carolinas in 1719. The Philadelphia area had a good number of wool weavers, and by judging the fact in the 1760s it had twelve fulling (wool furnishing) mills. There were sufficient silk weavers to warrant the construction of another silk reeling mill in 1770, treating cocoons raised in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and New Jersey.

Linen weaving also increased dramatically. In 1752 Benjamin Franklin reported to the English Parliament that the 70,000 bushels of flax seed that were exported to England had all been made into coarse linen. By 1760 Philadelphia was the largest and wealthiest North American city with 22,000 residents. As the principal North American port and trade center, the area held the greatest concentration of textile manufacture on the North American continent.

Wherever there are permanent settlements you will find professional populations. There were professional wool carders, combers, fullers, spinners, weavers and dyers. The textile industry like other industries became an ad hoc basis. Farming families often did everything right on their farms. The guild system that became so entrenched in Britain did not take root in America. This will later become a reason for our success in so many other areas.

Sample of a coverlet from Tennessee dated to 1823. Comment that goes with the scan" "Woven on a four shaft loom in white cotton and dark blue and red wool, this overshot coverlet was made in Tennessee. Dated examples of this type of coverlet survive from as early as 1773, though this example dates from some 50 years later."

THE REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD (1765 - 1800)

The early definition of "quilts" as we know the definition of today, may be challenged to actually refer to quilted petticoats. Many petticoats were made of whole cloth fabric...thus, they may have been the source for so many whole cloth quilts. The petticoats were designed to be shown under a split skirt (the split was in front). The fashion for exposed quilted petticoats was between 1750 and 1758. We know that there are at least two quilts that has survived the years since then. The quilts were dated 1750 and the other 1758. Quite often the petticoats were made of silk or glazed wool, quilted with such designs as feathers and flowers.

From letters dating back to this period, we are able to reread that in 1770 a Boston schoolgirls named Anna Green Winslow wrote to her mother asking if she might give her "old black quilt to Mrs. Kuhn for aunt said it is never worthwhile to take the pains to mend it again".

References to bed quilts with patchwork designs do not appear the 18th century. Quilt appraisers in Kent County, Maryland used the term "patched" to refer to a quilt in 1760. Rebecca Armory living in Boston in 1763 advertised that she sold English and India patches (these may have been intended for bedcovers...or to patch petticoats).

By 1726 the English writer Jonathan Swift referred to Gulliver's clothes as being "the patchwork made by the ladies of England, only mine were all of a color" (IE, could he be referring to "whole cloth"?)

Early colonial quilting patchwork basically falls into 2 different categories: Pieced scrap quilts and applique designs of cut out chintz. Often the central focus was a medallion format (in the center) with borders, or even a set of additional patchwork.

Sometimes the quilters would combine large scale chintzes with small scale prints and might add fabrics of different fibers. The early quilters have been known to use decorative techniques such as embroidery, applique and piecing in the same quilt.

The early quilter would often use floral motifs, stars, borders of vines or swags, even Jacobean crewel embroidery. They even used counted stitch samplers and Indian palampores. Tracing back to whole cloth bed quilts, we can see that plain motifs like grids, parallel line, even feathers and pomegranates.

We also know that the piecing and applique work was one job and that the actual quilting was done by another person.

Patriotic fever increased as a direct result of the Stamp Act of 1765. Local textile makers began to be seen as another means to independence (but not by everyone). Until 1775 and after the Revolution many patriotic and philanthropic and philosophical societies sponsored attempts to establish more efficient textile manufacture. Several innovations for multi spindle and reeling machines were invented.

Three elements held the newly formed United States of America back for 20 years. Britain made huge developments in the mass production of cotton yarns, with a consequent increase in their being exported to the colonies, together with British mixed cotton cloths, which had appeared in North America since the 1750's. The second hold back was the Revolution. The revolution interrupted the supply of British textiles from 1775 to 1783, it also hindered the attempts to merchandise in America and served to reinforce the value of home production. The third event occurred in 1784 when British manufacturers flooded the North American market with newly perfected all cotton cloths printed with fashionable patterns. In retrospect what the British were doing was dumping goods on the American market causing US goods to fall in value. Given the 20/20 hindsight what the British were doing is known as Predatory Pricing. In our world as we know it today, this is illegal.

Philadelphia continues to be the hub of textile manufacturing. Weaving continues to play an important role. In the street indexes of 1785-1800 170 people were considered as professional weavers. One third made stockings, and a handful specialized in lace (braid), fringe, silk or carpet weaving. There were fewer than 10 printers among them was John Hewson who print works had been in business before the Revolution and existed into the next century.

The Philadelphia pattern was duplicated on a small scale in other growing communities, including around Boston. In Beverly, Massachusetts a totally integrated mill (combing, hand carding, spinning, weaving) was founded by George Cabot in 1787 and until the early 1800's made a wide variety of cotton cloths including corduroy, jean, denim, marseilles (double cloth) quilting, muslin, and dimity.

By 1790 Samuel Slater, an Englishman working for Almy and Brown, succeeded in establishing the first water powered cotton spinning mill in Providence, Rhode Island In 1793, Eli Whitney perfected the cotton gin (this strips the fibers from the cotton seeds). This invention sets into motion the development of vast plantations of upland cotton.

1800-1860

Slater's water powered spinning loom soon encouraged others. By 1800, 7 others built, 213 were built by 1815. They were clustered along the many rivers In Connecticut, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and southern Massachusetts. With all of the new inventions weaving was still done by hand as an out worker (IE, piecework basis). The first efficient power looms still wove only plain cloth; even in the 1820's simple cotton fabrics like ginghams were still being woven by hand. The installation of power looms coincided with a "boom period" caused the War of 1812. The War of 1812 caused a sharp demand for locally produced textile goods. Francis Cabot Lowell, the nephew of the inventor of the integrated mill had toured England in 1810 to 1812 and saw power looms in operation. He returned to America and constructed his own version by 1815 in Waltham, Massachusetts.

Lowell made a few changes: He placed a professional manager in place of an owner manager and used subcontracted selling agents. This changed the his venture from the "Rhode Island system". The Lowell organization was so successful that five years after Lowell's death in 1817 his associated developed a new location north of Boston where the water power was capable of running dozens of mills. Later the name of the town was named "Lowell" and it became the largest textile manufacturing cities and became a model for others to follow. This became known as the "Waltham System".

Rapid development of other sites occurred between 1820 and 1860. By 1850 there were 896 power driven mills in place in New England. There were almost 500 mills based on the "Waltham System" in northern Massachusetts.

This growth reflected the threefold increase in the population and the wealth in the US since the early 1800's. There were a number of serious "depressions" (we may call them "recessions") which followed the end of the War of 1812 (when British textile producers flooded America with cheap textiles), there were also depressions in the seventh or eighth year of each succeeding decade during that period. One reason for the depression was the huge increase of cotton production in the Southern States. In 1801 the total output of cotton in bales was only 100,000. By the year 1820 the meager output rose to 400,000 bales per year! Cotton was being grown in central Alabama, central Tennessee, the lower Mississippi. By 1860 the total output in bales was 4,000,000! Much of the cotton was being exported to England. By the 1840's 4,000 ships carrying American cotton were welcomes in European ports.

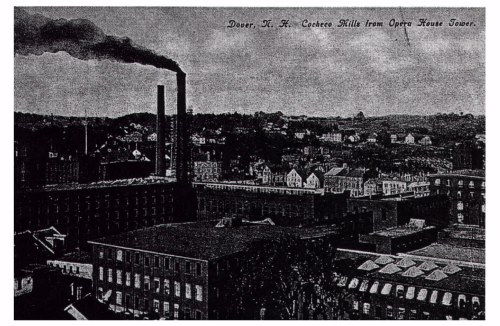

The New England and Philadelphia mills began to machine print cotton in the 1820s. In the 1810 Niles' Weekly Register claimed that the greatest concentration of cloth printing occurred in the 8 factories around Philadelphia, this is not surprising as the new firm of Thorp, Siddel and Company had just installed the first printing machines (one surface (raised wooden roller), the other engraved copper roller. In 1812 they produced 1.4 million yards. By 1832 the same district in north east Philadelphia County had 12 print works. Within a few years even the tiny state of Rhode Island had a great number of printers among them Allen Print Works and Clyde Bleachery and Print Works, from which later examples of shirtings and dress fabrics. By 1820's important manufacturers into the 20 century: Merrimack Manufactory Company printing at Lowell from 1824; Dover Manufactory Company, in New Hampshire from about 1827 (later Cocheco Manufacturing Company) and Hamilton Print Works at Lowell from 1828.

Interesting side note: Some years ago the Cocheco line was reintroduced as reproduction textiles from 1880 to 1890. The line was reintroduced after some of the original fabric salesman cards were found in a vault at the American Textile History Museum.

Postcard of the Coheco Mills

Sample of an actual Coheco fabric label dated 1866

Scan of Coheco fabric card for the salesmen

Cocheco was very focused on producing the very best quality textiles with aslant towards sales. This includes Chinese motifs designed for the American market. This also included French peasants in scenes, Egyptian motifs, many inspired landscapes, children playing games, etc. All of this meant that Cocheco's 14 printing machines turned out some 40,000,000 yards of fabric per year. We are blessed in that Cocheco kept very precise records of its artwork, roller sets and finished prints. Even though each mill specialized in a format of its own, Cocheco kept records in bound volumes along with loose sheets that tracked the steps in the production process. A different set of records included the salesman's fabric cards (that are still used today) and samples were given to the salesmen to sell the Cocheco fabric line.

The marketing of the Cocheco fabric line was delegated to the Lawrence and Co's (they were the sales agent exclusive to Cocheco), their offices were located in Boston and New York. But Lawrence and Company did much more than just sell fabric! They would talk to their customers and listen to their needs, they paid attention to the changing trends in fashion. They would design exclusive lines for their larger commercial buyers. They also organized the complete mill process with the mill superintendent. Every element in the printing of fabric from concept ideas to actual printing to delivery of the fabric was a part of the Lawrence and Company.

In the 1880's Lawrence began to sell fabric through agents who were not salesmen directly connected with the company. Lawrence and Company was very successful! Not only did Lawrence and Company sell fabric in the United States, but they also were among the first to sell fabric in Argentina, Chile, etc.

In 1909 Cocheco was sold to Pacific Mills of Lawrence, MA. The printing operation was moved to Lawrence and also continued to manufacture cotton fabrics at Dover until about 1940's when the mill was closed.

Scan of the Allen Print works factory about the time of 1830's. Notice that to the left you see the man with his hand raised with a hammer in his hand ready top strike the wood block: what he is doing is the actual printing of the fabric. In the middle you see the man holding the woodblock in his allowing the child to brush the dye on the woodblock. To the right, you see some women doing what is termed as "penciling" (using colored pencils to add additional colors and details). Hanging in the background you see the fabric after it has been printed and is drying.

Here's the copy that goes with it: "Discharge and semi discharge madder prints were produced in large quantities about 1835. This example of circa 1880 was roller printed by Allen Print Works, founded in Providence, Rhode Island in 1830-1. Such clothing cottons with small patterns became known as "calicoes".

Some of the early roller patterns were brought from England. By 1825 they were increasingly made in America.

In the middle decades of the 19th century the majority of fabric designers were English. Some were hired in England by American mill owners, but the patterns were closely developed after the French. In the 1840's for example, J. Biggs and Company (in Frankfort, 6 miles north of Philadelphia) used patterns that were supplied by John and William Ashton, designers from England to supply their two four color and their four six color machines. The Ashton designs followed after the French silks, vestings and prints (especially lightweight wools (or delaines, which were highly fashionable), and their patterns had French names, with the result being that many people thought that their prints were foreign. Today this would be considered a fraudulent practice and the mill might have been heavily fined by our government.

COVERLETS

The mechanization of cotton printing coincided with the period during which patchwork and applique' superseded the making of embroidered or whole work coverlets, as well as quilted (whole cloth) or pieced (but plain fabric) coverlets, which had been well established in the 18th century, and typically used home woven linsey-woolsey (a mixture of linen and wool).

Applique' and patchwork, already a sophisticated American art in the last quarter in the 18th century, relied 'for best' on imported cottons and this remained true into the 1820's. With the many mechanizing of the textile industry, the price of fabric dropped from about 23 cents per yard in 1825 to 12 cents in 1840. Because of the drop in price, small calico and larger floral prints could easily be purchased (rather than salvaged). This also meant that the local quilters in those areas could develop their own patterns and color combinations. The Amish maintained their own use of plain fabric pieces in nonfigurative patterns.

The Pennsylvania Germans were among the first to introduce calicoes into their colored patchworks. The "Pennsylvania Dutch" used stylized tulips, feathers, birds, hearts, sunbursts that had symbolic meaning within their culture.

The Civil War to World War 1

The Civil War had both long and short term effect on textiles. In the shirt term, the supply of cotton. The shortage harmed cotton mills both in the US and Europe, but gave a boost to the production of woolen cloths (both printed and woven) as well as waste yarn spinning and the use of hemp, linen and silk. These were often combined with cotton. For several decades many American cloths had a slubbed, textured or 'fuzzy' surface, especially when waste yarns were used.

The growth of the silkworm industry had collapsed in 1840, was revived in California, to no avail. By 1860 only the Cheney Brothers' silk processing firm in Manchester, Connecticut. Manufacturers returned to using European supplies during the Civil War, but by 1867 the Pacific Mail Steamship Company opened a direct service to China, and a new American silk industry began to develop, with New York becoming one of the largest silk markets in the world. By World War 1 America had far outdistanced France in its consumption of silk, mainly for stockings, and the industry also provided the firm base on which the manmade fiber industry was to develop.

The cotton shortage forced many firms to streamline. Many of the multi fiber and multi process mills were far less numerous after the Civil War. Large factory complexes in the North continued to expand, but they concentrated on one fiber or product. The Boston-Providence area dominated throughout this period. Fall River became the leading cotton cloth producers, with fine cotton weaving dominated by New Bedford. Lawrence was the center for worsted cloths; and Lowell, the site of the Hamilton and Cocheco mills for printed fabrics. Paterson, New Jersey aided by the influx of French workers became America's silk (producing 50,000,000 worth of goods in 1909), while Philadelphia grew dominant in the use of wool for hosiery, knitted goods, carpets and upholstery cloths. The heart of this trade was New York, which dominated clothing manufacture and distribution, the latter from Worth Street.

The Southern States were slow to recover after the Civil War. Cotton levels slowly grew to where they were before the Civil War. After the Civil War, though the southern mills still needed supplies and workers and technicians, the southern mills often developed and implemented new ideas. One example is Sawyers high speed ring spinning machines which were suited to coarse cotton yarns. One such business that was built on this technology was the Cannon Mills of Concord, NC. J. W. Cannon founded the business and within 60 years it was the world's largest supplier of household textiles and furnishing fabrics. A few of the reasons for their success was the location of steam power, the proximity of cotton (and coal for fuel) and the labor surplus created by the Reconstruction. The workers were poor whites who were willing to work for low pay. By the 1880's labor was a major factor, while the 10 hour day was becoming a reality in northern mills and the minimum age rose to 13, neither of these practices, nor night work for women and children (gone from the north by about 1900), was banned in the south until 1933.

In the decades before World War 1 the Northern workers rebelled against their worsening working and living conditions. There were some 24,000 strikes between 1880 and 1900. The worse strikes were yet to come. The Fall River strike of 1904 shut 85 mills for 6 months. Almost half the workforce left the city. Eight years later a strike closed all the mills in Lawrence (where American Woolen in 1905 built the largest cloth factory covering 30 acres). The workers won higher wages, and their victory boosted organized labor though out the industry. World War 1 created a temporary boom, but in the depression that followed its conclusion Lawrence was stricken by a further 5 month strike in 1919, a year after the widespread United Textile Worker's strike and in 1922 further wage cuts brought out workers in Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Maine.

Throughout this period southern production quietly and steadily grew. By the turn of the century there were well over 50 southern mills, among them Dan River Mills (founded in 1882 in Danville, Virginia) and 7 in Spray and Draper (North Carolina) that in 1902 began producing for Marshall Field and Company and in the mid 1930's became Fieldcrest Mills. Initially their product was cotton towels, sheeting and print cloth or the cotton "plaids" long made in Northern factories for the southern and western markets. Northern mills continued to supply higher quality goods; prints ranged from lightweight cotton dotted with bicycles to sturdy cretonnes with patterns influenced by William Morris' designs; in Philadelphia mills were using new machines to make elaborate furnishing moquettes and plushes to deep glowing shades.

The Lawrence School of Design was established in 1872, and within a few years a Frenchman by the name of Charles Kastner (a former print designer for Pacific Mills in Lawrence) was training designers of prints and weaves. The Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876 inspired the foundation of a School of Industrial Art; by the 1880's there were also two design schools in New York, where its distributors, agents and garment makers increasingly influenced design decisions. To improve public taste are education for school children was widely mooted. In matters of taste the Centennial had revived the colonial style, restoring with it the fashion for home weaving and patchwork quilting (neither of which had disappeared). Out of the discussion surrounding appropriate industrial design with an independent American style came a lively arts and crafts movement, which set into motion a number of decorative art societies from New York (1877 cofounded by Candice Wheeler (1827 to 1923), who from 1883 to 1907 designed and produced textiles through Associated Artists) to California (where the Women Artist's Association in the 1900's was largely composed of weavers) and back to Montreal (where the Canadian Handicrafts Guild was founded in 1905). Member of such organizations were offered contact with firms such as Cheney Brothers, Marshall Field through the joint efforts of Women's Wear Daily and the American Museum of Natural History, which from 1916 sponsored a series of competitions and educational programs. By 1919 a member of the Museum's staff recorded that American designed goods were selling in the discriminating markets of Paris and London.

NATIVE AMERICANS

Native Americans didn't make quilts, per se. But they were designers of some of the most beautiful blankets. Sometimes, the Native Americans did design their own textiles, but this came after trading with the White settlers. At least it was not until the trading with White settlers that cotton was introduced to the Native Americans. Previously the Native Americans used wool, plus tanned hides as clothing.

The Native Americans did use dye to only dye wool, they also dyed feathers, hides, basketry materials, etc.

Since they used wool, they chose to dye the wool before weaving the wool into textiles. Interestingly, the Native Americans used many dye plants that were on their Reservations.

Some of the plants required mordants for colorfastness and that depended on the color. Some mordants were plants and still others were minerals (in the desert regions).

Wolf Moss (a lichen, Evernia vulpina) seldom required a mordant. Another lichen that didn't need a mordant was Ground Lichen (Parmelia molluscula). Many rock lichens that yielded a fine red color also were non fading.

For the desert dwellers, Alunite (a mineral) was extensively used as a mordant. Not only did the desert dwellers use Alunite they used the madder plant and other plants for dyeing. The plant product was boiled until the right color or shade was reached. The problem was that if the plant boiled too long, then the dye would change a color from the original color that was needed. This is true of the madder plant. If it is boiled too long, the dye turns from the beautiful red to yellow.

For the Plains area dwellers the Alum root (Heuchera glabella) was used not only as a mordant but also for medicine. They used 2 finger lengths of the root to largest dishpan of dye was satisfactory.

If the dye needed to be transported over long distances, the Native Americans would travel to the place bringing their items in a dried form. Then the dye was processed on the spot. This meant that the many dyes which were used to dye items, the stalk, seeds, roots and plants, etc. had to be soaked at least over night.

Native plants that were not fixed with a mordant have the advantage in that when they do fade, they always fade in their own color scale. IE, a red color might fade to another red color, not to a brown. Another positive effect is that the dyes that were used with out a commercial mordant also does not oxidize, IE that the fabric literally is "eaten" by the process of oxidization. That is one of the problems with quilts that were dyed with commercial dyes...the minerals used in the dye process literally destroyed the quilt over time. This type of damage is hard to repair. Every piece of the oxidized fabric would have to be replaced.

Black color was achieved by using Bee Plant, Cleome, pink flowered (Cloeme serrulata) (The Native Americans from New Mexico and Arizona would boil this plant until it was black and gummy. They called this "Guaco", according to research this color makes a really beautiful black. Also used were Three-lobed Sumac, Squaw bush (Rhus trilobata). Slender twigs of this shrub were rolled up with leaves and used either fresh or dry. Pitch from the pinyon and yellow ochre were added and all boiled together to make the finest Native American black dye.

Blue color was produced from Sandalwood, the Lost Blue of Araphos (Comandra padilla). Sky Rocket, Trumpet Phlox (Gilia aggregata), "Tem Paiute" has blue dye in its roots.

Violet was brought forth from the fruit of the Sarvis Berry or Service Berry. They also used Antelope brush (Purshia tridentata), "Hunabe" also gives a beautiful violet from ripe seeds coats that have been cooked. "Mountain Mahogany" (Cercocarpus ledifolius), the inner bark produced a purple dye.

Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) was used by the Paiute and Shoshone. They collected the bark, berries, needles for a brown tan dye. They also used the green juniper needles by burning them as a mordant. They used the ashes.

Green was processed from the leaves of the Mountain Ball Sage (Artemisia frigida). This made a soft pretty green.

Red came from "Conk" fungus (Echinodontia tinctoria). This fungus grows in conifers and makes a brilliant orange red dye as did the Choke Cherry (Prunus melanocarpa) this made a beautiful red. Cinquefoil (Potemtilla spp) was processed by cooking the whole plant which looks silvery, silky, for red dye. Madder (Galium boreale) Bedstraw gave a beautiful red from fine roots. This was especially good for wool, quills or horsehair. But if it is boiled too long, will turn yellow. Mountain Mahogany (see above notes) also gives a rose-red dye from the nodules on its roots. The Three lobed Sumac if you use the bark in the Mountain areas with leaves gives a red-brown Berries on wool gives a dusty pink color. Berries mashed and fermented, NOT boiled. Rock lichens gives a red color if you scrape the lichens off right after a rain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Encyclopedia Britannica

A history of Printed Textiles, Robinson, Stuart, Published by MIT (Cambridge, MA), 1969

E. W. Barber, WOMEN'S WORK, The First 20,000 Years, published by Norton Co, 1994

Jennifer Harris, TEXTILES 5,000 Years, published by Harry N. Abrams, 1993.

Schneider and Weiner in Cloth and Human Experience

Edith Van Allen Murphey, Indian Uses of Native Plants, published by Meyerbooks, 1990.

Hersh, Tandy, "Quilted Petticoats" Pieced by Mother: Symposium Papers (ed. Jeanette Lasansky). Oral Traditions Project, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, 1988. Page 6.

Winslow, Anna Green, A Boston School Girl of 1771, Edited by Alice Morse Earl, reprinted by Singing Tree Press, Detroit, Michigan, 1970, page 5

Gloria Seaman Allen, "Bed Coverings, Kent County, Maryland 1710-1820". Uncoverings 1985, American Quilt Study Group, Mill Valley, California, 1986, page 20.

Murray, James, A. H; Henry Bradley; W. A. Craigie and C. T. Onions; (editors), Oxford English Dictionary, Clarendon Press, Oxford, England, 1933, page 548